The Crab Nebula, Messier’s first object

TARGETS. How this guest star became a main character in our night sky.

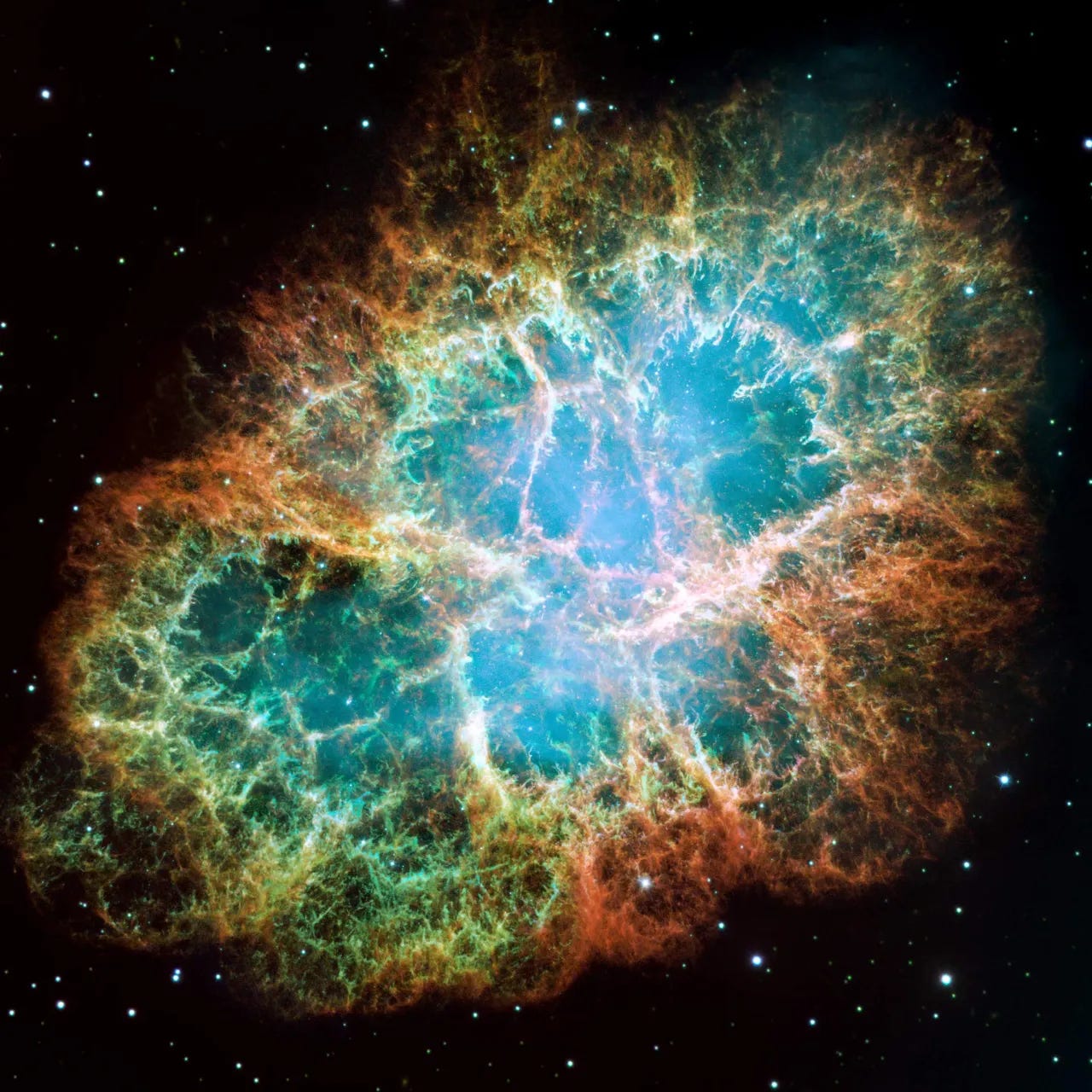

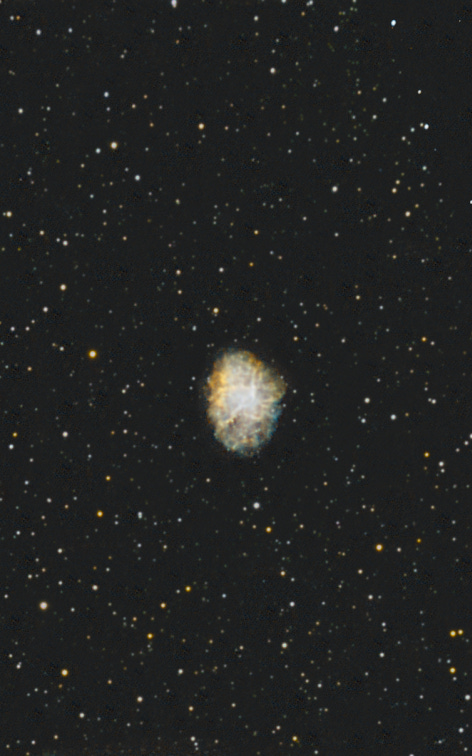

Not only does the Crab (Messier 1 or M1) look completely wild – like somewhere in there an evenly-matched pair of space wizards is battling it out and the kedavras are flying – but this mysterious and alluring nebula has also played a remarkable role in astronomy history.

The story begins in AD 1054 China, in the 32nd year of much-loved Emperor Renzong’s reign upon the Dragon Throne. The Northern Song Dynasty stands at its pinnacle. Imperial capital city Bianjing – a thriving, walled garden of palaces, canals and imposing pagodas – might at this point just be the world’s foremost hub for intellectual pursuits: art and literature but also technology (the first movable type, cast in ceramic!) as well as the proto-sciences – not least among them astronomy.

So the Song Empire finds itself particularly well prepared when in July of that year there appears in the sky a spectacular surprise. A dazzling light, in the modern constellation Taurus, the Bull. Brighter than Venus; bright enough in fact to be seen in the daytime for the better part of a month. Even after it fades from the day sky, it remains visible to the naked eye by night for more than a year and a half. Renzong’s imperial astronomers (they even have a “Bureau of Astronomy”, how cool is that!?) are certainly excited but far from shocked. Because they’ve read about this phenomenon before, in chronicles handed down by their ancestors, who also gave it a name – and the astronomers diligently set about making observations, writing down detailed records for their own posterity on the position and nature of this new “guest star” – what we today would call a supernova.

Fast forward 700 years, to the 1750s and the Hôtel de Cluny in central Paris (no suffering on frigid mountaintops for pre-Industrial astronomers, thanks to dark city skies). Eager young comet-hunter Charles Messier is perched at his refractor, on the lookout for the return of Halley’s Comet, predicted to reappear in the constellation Taurus, when he spots a promising puff in his eyepiece. Though his initial excitement sours when he realizes the little cloud isn’t moving, and therefore not his longed-for comet. But Messier quickly decides to make citron pressé out of this particular lemon: why not catalog fixed objects like this from now on, not for their own sake, but to help him avoid them when searching for comets? Thus is born the Messier Catalog, Charles Messier’s greatest (accidental) contribution to science, and a major reference for astronomers to this day – initially as a list of what not to look at – beginning with M1, the Crab Nebula (more about that name below!).

Our final stop for this story is 1920s California, where powerful new telescopes are unleashing an astronomical revolution. Based on other recent observers noting changes in M1, John Charles Duncan relies on photographic plates, taken eleven and a half years apart with the 60-inch reflector high atop Mt. Wilson near Pasadena (the days of observing from cozy haunts in the center of major cities now long gone), to prove definitively the nebula is expanding. Later, his colleague Edwin Hubble suggests the Crab might actually be related to the supernova observed by the Song astronomers in 1054. A notion debated until the late 1930s/early 40s, when Nicholas Mayall of the Lick Observatory near San Jose, by extrapolating the nebula’s growth rate backward in time nearly 900 years, finally proves it’s indeed a remnant of that earlier explosion. This makes the Crab Nebula the first deep sky object to be connected to a historical supernova, kicking off a (successful) hunt for several more.

Favorite facts about the Crab Nebula

The Crab Nebula (M1) looms in space roughly 6500 light-years from Earth, with a diameter of approximately 6 light-years (about 3 times the width of our solar system, including the Oort Cloud).

At its heart remains the final vestige of its original star, now reduced to an ultra-dense neutron star just 30 km in diameter and rotating at a terrifying 30 times per second. This Crab Pulsar emits massive amounts of radiation across a wide spectral range.

Thanks to its proximity, intriguing nature, and precisely-documented history, M1 has been the subject of much scientific study, including into the development of supernova remnants and the nature of pulsars.

And finally: the name… is actually pretty random. Apparently it’s down to a sketch made by English astronomer Lord Rosse while observing it in the 1840s, and over time the name just stuck. Personally, I think his sketch looks more like a mutant pineapple (but then that wouldn’t be quite as catchy). What do you see?

How I looked at it

M1 is one of the most popular and accessible targets in the night sky, so all you need to do is select it in your star atlas and tap “go”. But, it’s good to be aware: as a nebula – even though it’s a bright one – the Crab is a bit more subtle. Unless you’re in a very dark location, you’ll be unlikely to see much of its dramatic color and detail in your initial live stack. So this is a target where a little processing (using digital tools to enhance your image) can be well worthwhile.

One proven option is to try a desktop-based app like PixInsight (quite expensive) or Siril (FREE!). These “post processing” tools help improve your image once it’s acquired. There is a bit of a learning curve in going this route, but for a modest time investment your final results can be dramatic. If you’re interested in trying post processing with Siril, I recommend the tutorial series by Deep Space Astro.

But what if a person doesn’t feel like sliding down the slippery post-processing slope just yet? Well, with my Seestar S50, I’m now able to make a number of image enhancements even during live stacking, including exposure, contrast and color saturation adjustments, as well as denoising (smooths the salt-and-pepper pixelation that’s a normal artifact of digital sensors). These features are awesome, but ZWO has included an additional tool which goes even further toward full post processing: Deep Sky Stack. This tool offers the same enhancements, but allows you to exclude individual sub frames you don’t like for whatever reason, and to combine subs from multiple sessions, potentially from across a number of nights. In other words, your final image can continue to get better and better, the more times you observe the target.

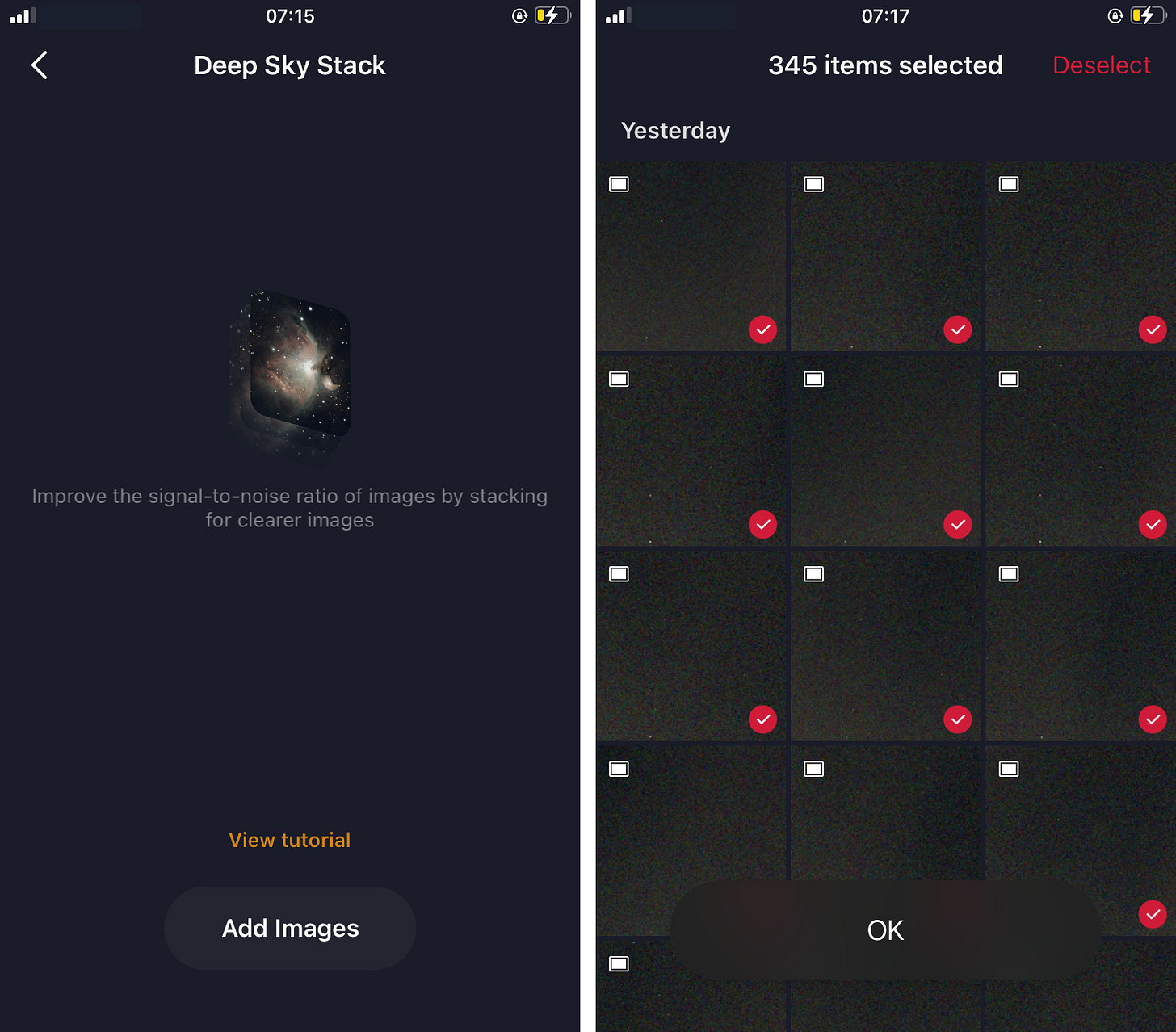

In this section I take a quick look at how to use the Seestar’s Deep Sky Stack feature. ZWO includes a tutorial right in the Seestar app, so I’ll just cover key steps here:

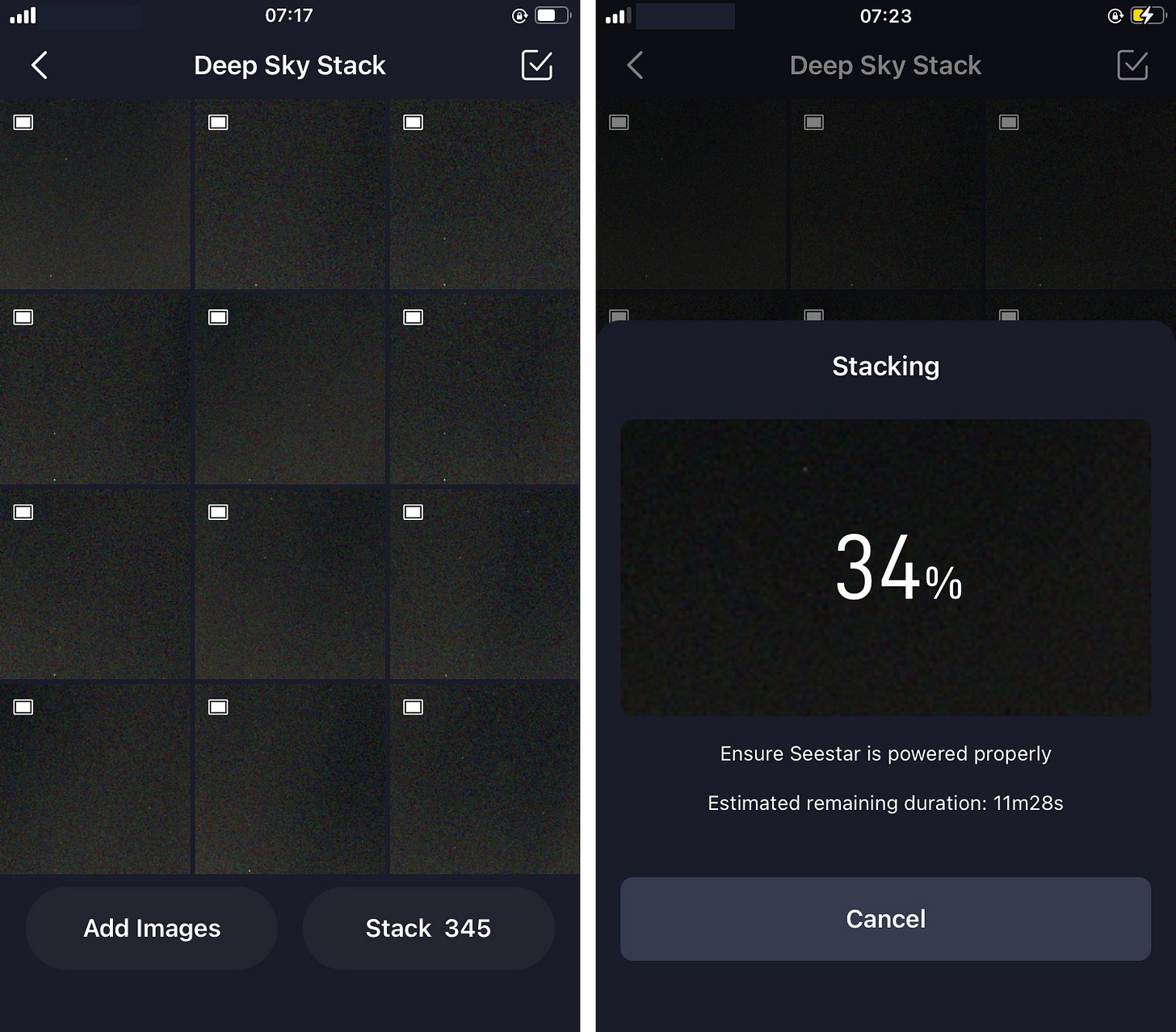

Selecting Deep Sky Stack from the Seestar app main page opens the processing tool (l). Tap the Add Images button to get started, then select the target to process from the folder list. A sub frame selector screen comes next (r). Either select All, or choose individual subs. When you’re all set, tap the OK button.

Back on the Deep Sky Stack main screen (l), tap the Stack button (it’ll also show the number of subs you selected to stack). Based on how many subs you chose, the app will estimate the time required to stack (r).

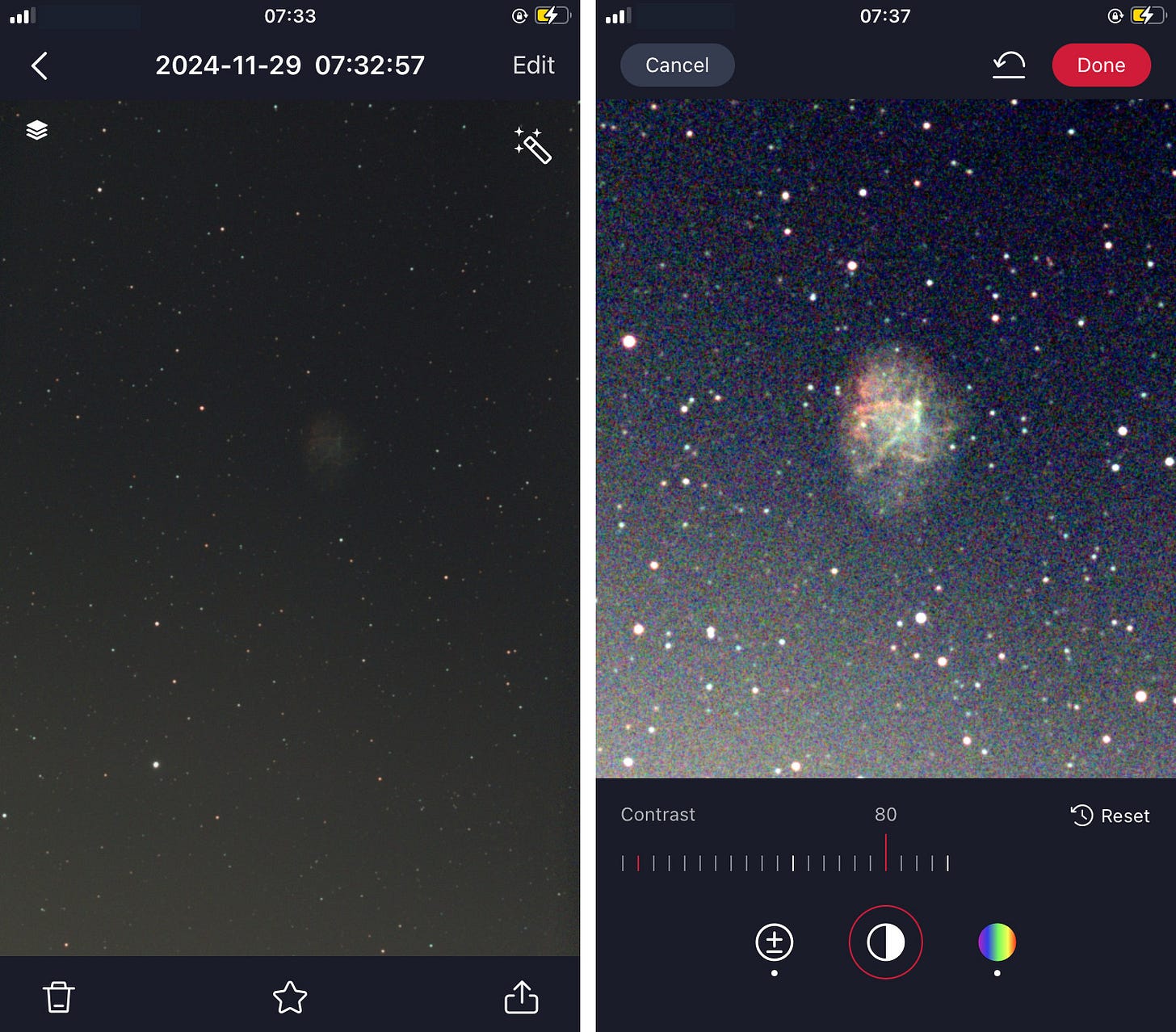

When stacking is complete, you’ll see the initial stacked image (l). Notice the Edit option and magic wand icon in the upper right corner. Tap Edit. On the Edit screen (r), adjust exposure, contrast, and saturation. There is no right answer here. Experiment with the image until you arrive at the result you like best. Note that throughout this section you can zoom in/out by using two fingers and spreading/pinching. When ready, tap the Done button.

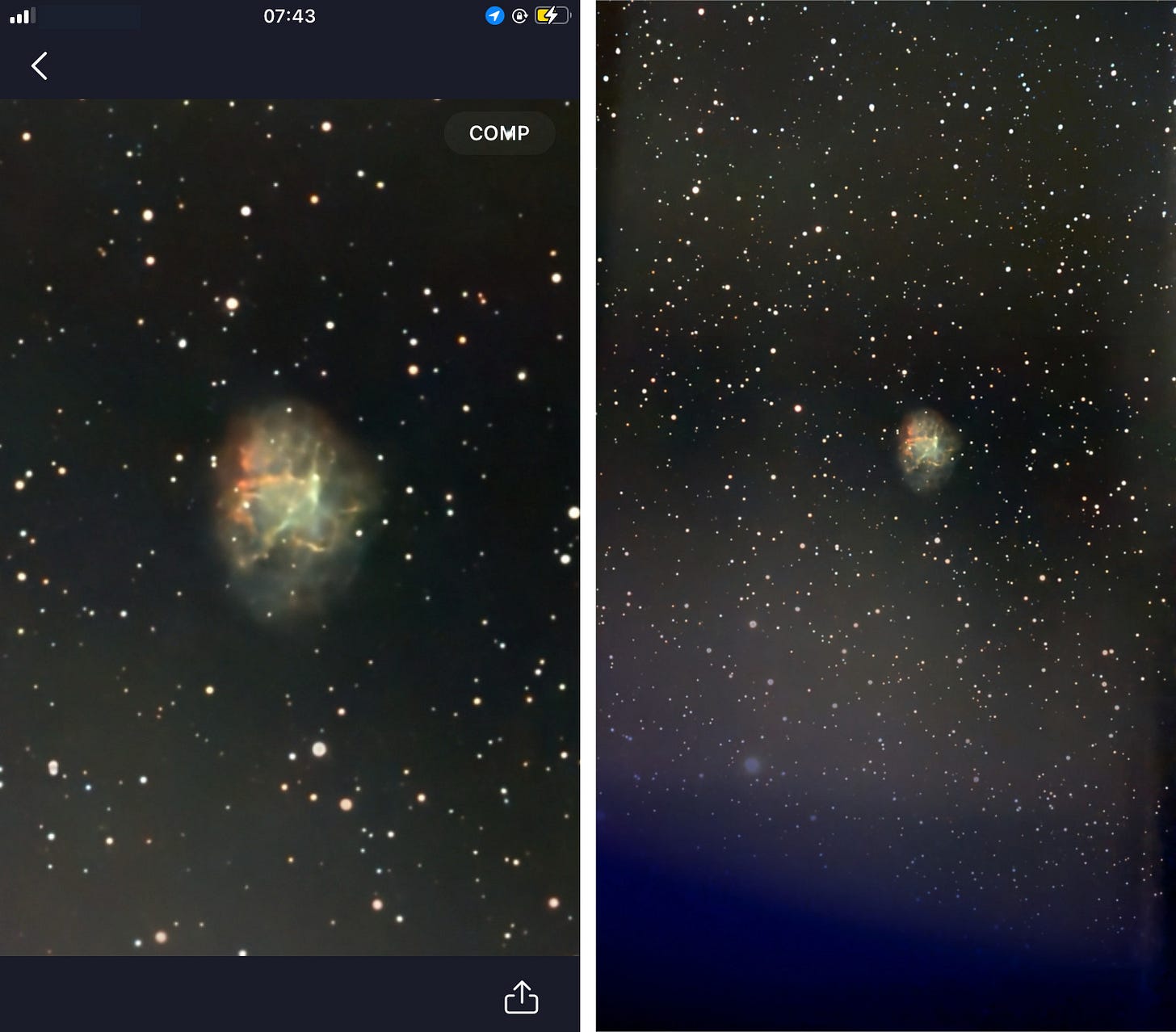

Now, back at the stacked image screen, denoise your edited image by tapping the magic wand icon. The app will complete this step in around 15 seconds, yielding a much “smoother” picture (l). Tap the up arrow icon in the lower right corner, then Download to add this fully processed image to your photo library (r).

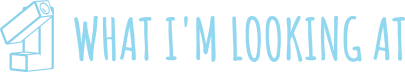

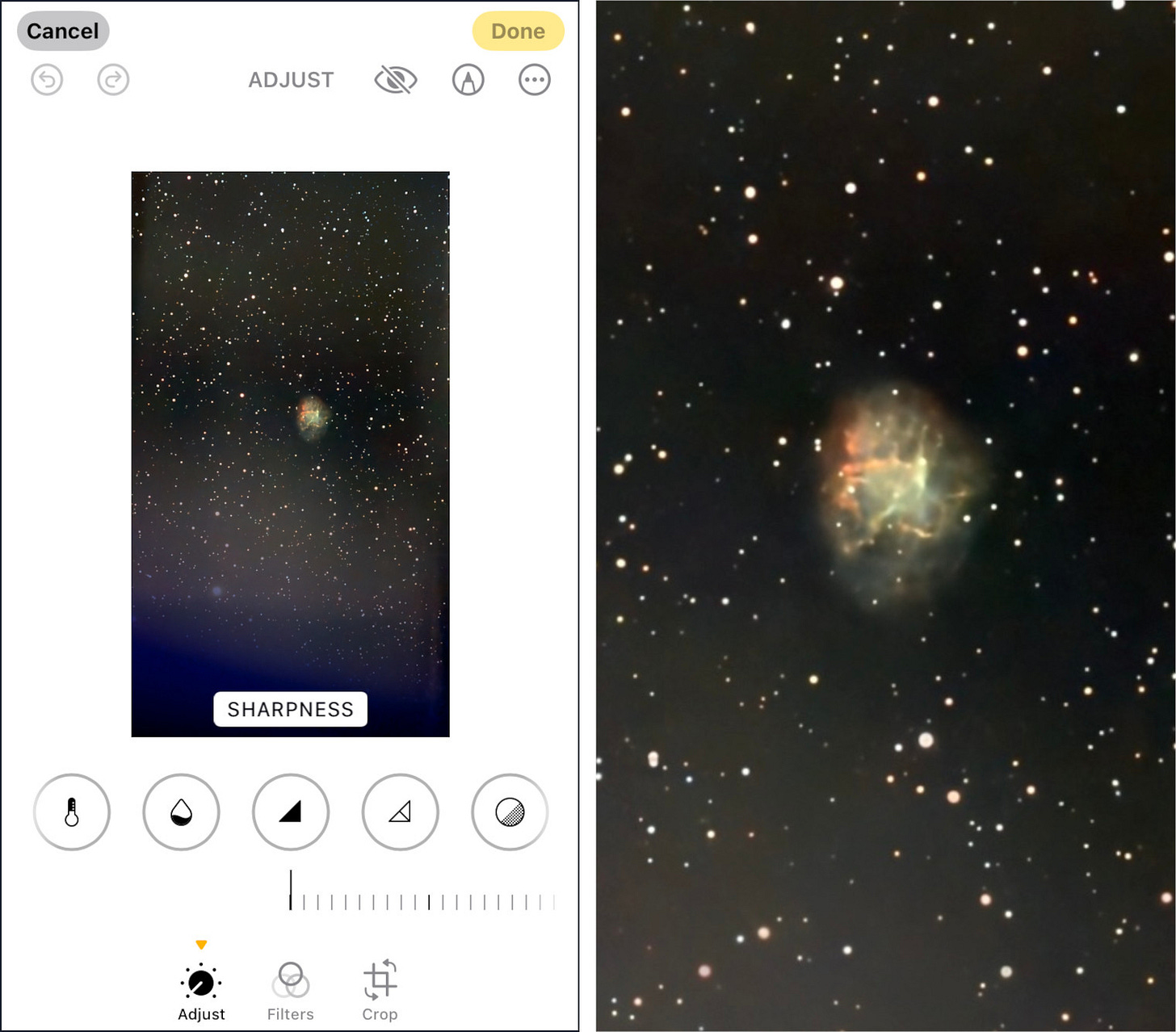

Finally, you can make further improvements to your image with your device’s own image editing tools. In my iPhone’s Photos app (l), I cropped my image and made tweaks to highlights, sharpness and definition. The finished result (r) clearly captures the nebula’s rapidly spreading tendrils and vibrant colors.

Note: before using Deep Sky Stack you must – prior to observing – tell your Seestar to save individual sub frames. To do this, from the Seestar app main page, first tap the Me icon (lower right corner), then Advanced Feature >, and lastly make sure Save each frame in enhancing is set to on.

Update: I shot the above image from central Los Angeles, which has some of the brightest night skies in the world, and still think it turned out great – so much to see there! But I also wanted to give the Seestar a chance to show what it can do with M1 under better conditions. So during December I collected around two total hours of data from dark sky locations, then processed the subs with Siril. Result below!

Best time to look

While the Crab Nebula is eminently viewable right now, it reaches its prime in January.

Bonus points

NASA: full-resolution giant Hubble mosaic of the Crab Nebula. Be sure to click “Zoom Image”, and then the criss-crossed arrows in the upper left corner of the screen to open the image in fullscreen. Wild indeed!

This great Astronomy article gets to the essential weirdness of M1. Favorite quote: “The Crab’s intense magnetic field acts as a drag, a brake, and slows the wildly spinning star while-U-wait. Eventually, the Crab Pulsar will whirl ‘just’ 17 times a second — with a flickering finally noticeable through amateur telescopes — by the year 4000.”

Did you know?

The Crab Nebula is such a powerful radiation emitter astronomers have sometimes used it like a galactic x-ray machine, taking advantage of serendipitous moments when it passed behind other targets of interest, like Saturn’s moon Titan, to learn new things about both foreground and background objects.

How did your Crab turn out, underdone or just right? I would love to hear. If you have an image or a story you’d like to share, mail me at patrick@whatimlookingat.com.

Fascinating! Thanks for taking the time to pull this info together for space no-nothings like me. 😊